Search

PHOTOGALLERY: Film & Brunch pre-premiere of film Redakce

The pre-premiere concluded with a discussion with Dominika Perlínová, editor of Respekt magazine, who spoke about the structure of the media environment in Ukraine, investigative journalism, and comparisons between Czech and foreign media, placing the film's themes in a real-world context based on her professional experience.

We would like to thank all viewers and look forward to seeing you at future screenings in Prague and the regions!

Submit your film to the 20th anniversary edition of the Pavel Koutecký Award 2026

PAVEL KOUTECKÝ AWARD FOR FEATURE-LENGTH DOCUMENTARY

The Pavel Koutecký Award for the first and second feature-length documentary film by a Czech director or a film produced in the Czech Republic is awarded to the director of the film and comes with a cash prize of CZK 50,000.

PAVEL KOUTECKÝ AWARD FOR SHORT DOCUMENTARY

The Pavel Koutecký Award for a short film by a Czech director or a film produced in the Czech Republic is awarded to the director of the film and comes with a cash prize of CZK 25,000.

WHEN AND WHERE?

February 9–11, 2026

Kino Kavalírka, Plzeňská 210, Prague 5

HOW TO SUBMIT YOUR FILM?

Via Filmfreeway or Google Form.

By submitting an application, the applicant confirms that they have read the Statute of the competition and agree with it.

If you have any questions, contact us at program@kinokavalirka.cz.

LOOKING FOR: Audiovisual Connect LAB Project Manager

Audiovisual Connect LAB is a European project led by the KRUTÓN association in cooperation with European partners. The project focuses on developing film literacy in Czechia and Europe. It focuses on working with data, concentrated testing of methodologies, teacher development, links with the film industry, and the implementation of a web platform.

What you will do

- Comprehensive project management in cooperation with the association's management: plan, milestones, budget in cooperation with the financial manager, cash flow, risks, reports (including documentation for the EU/Creative Europe).

- Coordination of European partners (SK, PL, HU, DE, NL, GR, UA) – regular online meetings, write-ups, agreements, monitoring of outputs.

- Implementation in CZ and SK: programming activities, production supervision, contracts, orders, accounting documentation.

- Organization of events in cooperation with production: workshops, trainings, network meetings, screenings, symposiums; logistics, production, subsequent billing.

- Administration in cooperation with the financial manager: data collection, monitoring of indicators, evaluation, archiving, grant obligations, EU publicity.

- Communication in cooperation with PR: with partners, lecturers, schools, and institutions; basic coordination of PR outputs.

- Content coordination: cooperation on methodologies and educational formats (audiovisual education). Expertise in this area is not required.

Who we are looking for

- You have experience in project management (ideally international/cultural-educational) and are able to monitor budgets and deadlines.

- You are able to write and read grant administration documents, prepare accounting documents and final reports in cooperation with the financial manager.

- You are strong in organization, independent, reliable, and able to handle multiple tasks at once.

- Languages: fluent Czech/Slovak and English (meetings, emails, minutes).

- You enjoy working with audiovisual education and are eager to connect schools, festivals, and experts.

- Plus points: experience with Creative Europe/EU projects, production of educational events, working with spreadsheets/databases.

What we offer

- Meaningful work in the Kavalírka and BOO team, professional growth.

- Cooperation for 2 years (30-40 hours/week), with the possibility of extension if both parties are satisfied.

- Access to a network of European partners, free admission to our events, and the opportunity to participate in other projects.

- A friendly team, financial remuneration commensurate with the cultural sector.

How to apply

Send your CV and a short cover letter (max. 1 page) to office@krutonfilm.cz.Please include your approximate availability (from when, how many hours per week) and a link to 1–2 relevant projects.

The selection process is ongoing. We will contact selected candidates to arrange an interview (in person at Kino Kavalírka).

KINGDOM OF SOUP BUBBLES

The rise and fall of the entrepreneurial Schicht family, founders of the Soap with the Stag brand

The film tells the story of the legendary soap with the stag brand and its founders, the entrepreneurial Schicht family, who over the course of three generations built a major soap and food production empire in Ústí nad Labem, contributing significantly to the development of the city and the entire region. It is also the story of their descendants, who search for their roots and a relationship to a city where none of them currently live, yet together they have purchased the neo-Baroque villa of their ancestors. The film reflects Czech-German history in the Ústí nad Labem region, recalling industrial growth and the pre-war coexistence of Czechs and Germans.

directed & screenplay by: Taťána Marková camera: Petr Vejslík sound: Vojtěch Knot sound design: Vladimír Chrastil music: Petr Tichý, Anna Romanovská editing: Šárka Sklenářová dramaturgy: Rebeka Bartůňková, Ivo Bystřičan, Katja Dringenberg executive producer: Jan Bodnár produced by: Jarmila Poláková (F&S), Martina Šantavá (ČT) co-produced by: Česká televize, krutón

About the director:

Taťána Marková is the director of three documentaries produced by Film & Sociologie – Revolution Girls (2009, One World, AFO, Doc Europe III Portugal, shown on Czech Television), What to Tell the Kids? (2014, Febiofest Bratislava, shown on HBO ČR) and Libussa Unbound (2019, 8th Indian Cine Film Festival and 5th Indian World Festival Honorable Jury Mentions, shown on Czech Television).

We call him BOO. Our new film festival released its programme!

The BOO International Short Film Festival will take place for the first time this November! You can look forward to films from Berlinale, Sundance, Clermont-Ferrand, and Cannes, Oscar-winning titles, new formats, and interactive programmes.

The main part of the festival will take place from 3 to 9 November at Kino Kavalírka, MeetFactory, DOX Centre for Contemporary Art, and other venues. This will be followed by school screenings at Kino Kavalírka from November 10 to 14.

The festival programme includes an overview by day, location and type of event – from film screenings and industry meetings to accompanying formats.

The complete programme, including information on accreditation, can be found at www.boofest.cz.

REDAKCE

After a forest is set on fire, a young scientist becomes a journalist to uncover the truth behind the flames.

directed by: Roman Bondarčuk screenplay: Roman Bondarčuk, Darja Averčenko, Alla Ťuťunnyk camera: Vadym Ilkov music: Anton Bajbakov editing: Viktor Onysko, Nikon Romančenko sound: Serhij Stepansky production: Darya Bassel (Moon Man), Darya Averčenko (South Films) co-produkce: Tanja Georgieva-Waldhauer (Elemag Pictures), Katarína Krnáčová (Silverart), Dagmar Sedláčková (MasterFilm)

About the director:

A graduate of Kyiv National University of Theater, Cinema, and Television, Roman has directed short films, documentaries, music videos and the feature film Volcano (2018), which premiered at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, screened at more than 50 festivals worldwide, and won 12 awards, including the Shevchenko National Prize, the highest state prize of Ukraine for works of culture and the arts. Roman’s feature-length documentary Ukrainian Sheriffs won the Special Jury Prize at International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) in 2015, Grand Prix of the IDFF Docs against Gravity, and was selected as the Ukrainian submission to the Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film. His second documentary, Dixie Land (2016), premiered at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in the USA and received a Golden Duke Award for Best Ukrainian Film at the Odesa International Film Festival.

VTÁČNIK

Capitalism from a bird's perspective

Vtáčnik is a small hill on the outskirts of Bratislava, which a few decades ago was decorated with vineyards and forests. For the director, like the other locals living there, it once represented a picturesque oasis of peace where birds took refuge. Today, however, it is being transformed beyond recognition by the cranes and excavators of property developers. Told from a detailed human and bird's eye perspective, this personal documentary composes an impartial mosaic of diverse, often conflicting accounts and ideas of what life in such a place should be like. Questions about economic concerns and the pursuit of a quality life in harmony with nature collide with the author's memories of her childhood.

directed by: Eva Križková dramaturgy: Martin Gogola ml. camera: Martin Jurči music: Martin Ožvold editing: Hana Dvořáčková sound: Tobiáš Potočný production: Silvia Panáková (dayhey) creative production: Biba Bohinská co-production: Jarmila Poláková (Film & Sociology)

SCREENINGS:

About the author

Eva Križková studied film studies at the Academy of Performing Arts in Bratislava. She is the co-founder of the film magazine KINEČKO and the distribution company Filmtopia. She is currently the director of the festival One World Slovakia. In 2018, she made the short film Fight as part of the Fest Film Lab workshop in Lisbon.

Satan Kingdom Babylon ON TOUR: pre-premiers in regions

Before the film's distribution premiere on October 16, 2025, we are organizing several exclusive regional screenings across the country, where the film will be personally presented by the director duo Marie & Petr Šprincl.

At each stop, Satan Kingdom Babylon Diaries will be available for purchase – a brochure consisting of notes from director Petr Šprincl's diary containing insights and experiences from filming among the hate groups.

September 22 from 8:30 p.m. – Kino Kavalírka (Prague 5, Plzeňská 210)

There will be a welcome drink on site, and the evening will be moderated by Ladislav Čumba. The screening will be followed by a discussion with the director duo Marie & Petr Šprincl.

Tickets on sale

Facebook Event

September 24 from 6:00 p.m. – Biograf Kotva (České Budějovice, Lidická tř. 2110)

The director duo Marie & Petr Šprincl will be present at the screening.

Tickets on sale

Satan Kingdom Babylon – Tickets on sale

Moravia, O Fair Land III – Tickets on sale

Facebook Event

September 30 from 8:00 p.m. – Kino Art as part of the Brno16 festival (Brno, Cihlářská 643/19)

The director duo Marie & Petr Šprincl will be present at the screening. The screening is part of the Brno16 festival program.

Tickets on sale

The director duo Marie & Petr Šprincl will be present at the screening.

Tickets on sale

The director duo Marie & Petr Šprincl will be present at the screening.

The director duo Marie & Petr Šprincl will be present at the screening.

Tickets on sale

Check out the interviews from Visegrad Audiovisual LAB

In September, as part of the Visegrad Audiovisual LAB Online project, we created a series of video interviews with experts from the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia specializing in audiovisual education and audience development, which is also the focus of a large part of the program at the upcoming BOO International Film Festival.

The guests share their experiences with developing a relationship towards film among children, young people, and adult audiences, educational approaches that connect film, art, and digital culture, as well as how to work with audiences across generations and media.

Milan Šimánek presents how Kino Art and the BRNO16 festival work with their audiences. He shares his experiences with audience changes and ways to reach new groups–from young people to seniors–without losing regular visitors. He also presents ways of collaborating with communities and schools, the importance of accompanying events, and how to create an original and attractive cinema or festival programme that attracts both new and regular viewers.

Karolina Śmigiel talks about the LET'S DOC festival and shares her experiences with film and audiovisual education. She also presents the value of documentary films for children and young people, the challenges of engaging young audiences, and the benefits that working with film brings not only to young people but also to teachers. She describes her approach to film education, her collaboration with young audiences at the festival, and the current challenges in film education in Poland and Europe.

Nóra Lakos shares her vision for developing film culture among children and young people in Hungary as part of the Cinemira festival. She describes the differences between creating and curating films for young audiences, working with audiences, including involving children and teenagers in co-creating festival activities. She presents strategies for audience development, cooperation with schools, and the educational benefits of workshops. She also talks about the role of filmmakers in shaping a film-literate generation and what is lacking in the field of supporting films for young audiences in the Visegrad countries.

Michal Kučerák shares his vision of digital and data literacy and its connection to film and audiovisual education. He describes the use of art and curatorship to better understand the digital environment, working with young audiences, and ways to engage audiences in educational activities. He presents strategies for making digital literacy accessible and interesting, collaboration between institutions, art, and film, and the benefits of these activities for audience development. He also talks about the challenges of working with educators and institutions and the future of audience engagement in the era of algorithms, platforms, and data.

The project is co-financed by the governments of Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia through Visegrad Grants from the International Visegrad Fund. The mission of the fund is to advance ideas for sustainable regional cooperation in Central Europe.

PHOTOGALLERY: Pre-premiere of Satan Kingdom Babylon in Venuše ve Švehlovce theater

On Sunday, August 24, the director duo Marie & Petr Šprincl presented their film Satan Kingdom Babylon to a full hall at the Venuše ve Švehlovce theater.

The evening was moderated by Ladislav Čumba, who also directed the subsequent debate accompanied by a raffle. Audience members had the chance to win vouchers for mini golf, an escape room, a bar, a restaurant, or a spa.

Thank you all for a wonderful evening, and we look forward to more special screenings!

International Day of Audiovisual Education at Kino Kavalírka on August 27

In the informal atmosphere of Kino Kavalírka and its garden, we looked at the changes in the new Framework Educational Program for Primary Education, which will newly include film and audiovisual education in primary school teaching, attended a networking of festivals for children and young people, or presented various programs of audiovisual education. The special guest of the day was Slovenian director Klemen Dvornik, who, in addition to a discussion about youth films, also presented his film Block 5.

The organizer and initiator of this international event was the KRUTÓN Association and the Audiovisual HUB Prague.

International Audiovisual Education Day was also held at the Audiovisual HUBs in Jihlava and Brno, at the Andrzej Wajda Film Culture Center in Warsaw, at the National Film Institute Hungary in Budapest, and at the Úsmev Cinema in Slovakia. The project is part of the Visegrad Audiovisual LAB.

Check out the photos from the event!

The project is co-financed by the governments of Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia through Visegrad Grants from the International Visegrad Fund. The mission of the fund is to advance ideas for sustainable regional cooperation in Central Europe.

We are expanding our communications team! – Junior Social Media Manager / Creator

The KRUTÓN Association is expanding its communications team! For audiovisual education projects, film distribution, and partly also Kino Kavalírka, we are looking for someone who can communicate diverse projects in an imaginative, sometimes humorous, and occasionally slightly bizarre way.

What awaits you here:

– Managing and creating content for Facebook & Instagram.

– Taking photos and shooting videos (a cell phone is enough, but if you can also use a DSLR camera – great!)

– Creating and submitting graphics.

– Participating in the creation of plans and strategies and their subsequent evaluation.

Who are we looking for:

– You have a flair for managing social media (FB, IG).

– You know how to work in Canva and can edit simple videos.

– You are creative, have an eye for visuals, and enjoy experimenting and searching for new forms of content.

– You can switch between different communication tones depending on the target audience.

– You can organize your work and stick to a plan.

– You can work flexibly for about 10–15 hours a week at Kino Kavalírka.

What we offer:

– An atmosphere full of inspiration, great movies, humor, and nice people.

– Flexible working hours – ideal for students, freelancers, or anyone looking for a creative side job.

– The opportunity to participate in building the brand of our projects.

If you think you're the right person for the job, send us your CV and cover letter by September 12 to radovan@kinokavalirka.cz.

Jana Minaříková

About me:

I prefer TV series to movies. I have been a member of KRUTÓN since 2021. I came to work in the cultural sphere indirectly, via work in the non-profit sector and then in professional gastronomy. Filip Kršiak invited me to collaborate on the Kino Kavalírka project at the very beginning of its planning.

I started as the daily manager of Kino Kavalírka and gradually took over the entire operation. I graduated with a bachelor's degree in Historical and Literary Studies from the Faculty of Arts at the University of Pardubice.

My favorites:

Passionate mushroom hunter, flower grower, cook, lover of coffee, gastronomy, cats and long hiking trips.

Kačka Šafaříková

About me:

I graduated from the University of Economics in Prague and Film Studies in Brno, thanks to which I spent one semester at Stockholm University. I have been involved in film production since 2012, and in recent years I have participated in films such as Tonda, Slávka a kouzelné světlo and Karavan. I have been working with KRUTÓN with various breaks since its founding, and I have been in charge of finances since 2023.

My favorites:

Scandinavia, hiking, reading, I enjoy film festivals – both as a viewer and contributor, films – Lost in Translation or Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, guilty pleasure – Taylor Swift.

Radka Hoffman

About me:

My history at KRUTÓN began in 2019, when I started working as a dramaturg for Young Film Fest. I gradually made my way into the industry and held various positions. I studied radio and television dramaturgy and screenwriting at JAMU in Brno, where I am currently completing my doctorate focused on contemporary cinema for young people in a European context. I am a member of the board of the European Children's Film Association, I previously worked for the Franz Kafka Society, and as a screenwriter I have collaborated with Czech Radio, Slovak Radio and Television, Storylab Audio, and the Center for Architecture and Urban Planning in Prague.

My favorites:

The sea, dancing, apricots, walks, stories, details, films, and daydreaming.

Adéla Lachoutová

About me:

I have always enjoyed films, especially documentaries and good sci-fi feature films. However, my first contact with filmmaking happened by chance. While studying social and cultural anthropology, we had the opportunity to learn about ethnographic film and shoot several short student ethnographic films. I was thrilled by the connection between film and research.

At KRUTÓN, thanks to the leadership of the audiovisual education department, I was able to delve into the secrets of teaching film education programs for children, which opened up a whole new and inspiring world for me. What I enjoy most about art, not just film, is combining different genres and types, which film education programmes allow me to do. In the audiovisual education department, I also take care of all projects for kindergartens, elementary and secondary schools, and teacher training. Last but not least, I coordinate the Audiovisual HUB Prague, where I can once again combine research with film.

My favorites:

Fire in the stove, books, coffee. View from the window of my cottage. Theater and Zelená hora..

Radovan Zajíc

About me:

I am a big film enthusiast who works in film marketing and PR. I have been a member of KRUTÓN since 2023. I started as the social media manager for Kino Kavalírka and gradually began to participate in almost all of our projects. In addition, I also work in the press department of the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. I graduated with a bachelor's degree in Arts Management from the Faculty of Business Administration at the University of Economics in Prague and am currently studying for a master's degree in Media Studies at the Faculty of Social Sciences at Charles University.

My favorites:

Hotels, collecting DVDs & CDs, tiramisu, Frank Ocean, Taiwan and Harry Potter.

Ellyn Černochová

About me:

At KRUTÓN, where I have been a member since January 2025, I take care of everything related to film distribution, primarily the educational audiovisual projects Young & Short and the international distribution project Cinemini. I participate in organizing events related to these projects, such as selection days and premieres, secure film licenses, and coordinate promotional activities. I am also gradually getting involved in the feature films we distribute, currently Satan Kingdom Babylon.

I studied Film Theory and History at Masaryk University in Brno, followed by a master's degree in Production at FAMU.

My favorites:

I love long car trips, camping, and white chocolate. I can't pick just one favorite film, but it would be something by Truffaut, Tati, Spielberg, Kubrick, or Jodorowsky.

Vojtěch Novotný

About me:

I have been intensely interested in films since childhood – both as a viewer and creator. I completed two semesters of film studies at Charles University's Faculty of Arts, then studied feature film directing at FAMU. I have been involved in KRUTÓN's activities since 2020.

My favorites:

Films, football and literature.

Eliška Šimková

About me:

My interest in film began in childhood, when my parents wouldn't let me watch the Disney Channel, so I watched things like Sophie's Choice instead. I have been a member of KRUTÓN since 2024. I started as an internee at the ELBE DOCK festival, where I was in charge of the accompanying programme. I got into cultural work through volunteering at festivals and mainly thanks to my studies. I graduated in International Relations from the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen and am currently studying Production at FAMU.

My favorites:

I have too many houseplants, I like to go to the mountains with my green backpack, and my not-so-guilty pleasure is Ústí nad Labem, where I come from.

Lenka Grussmannová

About me:

I studied French philology at Charles University and the University of South Bohemia, spent almost six years in administration at the French Lycée in Prague, and then took another six years of parental leave.

My favorites:

Trips, maps and tourist signs, photography, public transport, Lieutenant Columbo, blueberries with Salko, black tea with lemon, theater for children, occasional music productions.

Martin Foltýn

About me:

After many years of occasional collaboration with the KRUTÓN, I accepted the challenge of becoming a full member of the team in January 2025. Since my student years, I have been straddling the worlds of IT and cultural events in the field of film festivals. After studying computer science at the University of Economics in Prague, I moved to Brno, where I earned a bachelor's degree in Theory and History of Film and Audiovisual Culture at the Faculty of Arts of Masaryk University.

My favorites:

Listening to music on the tram, at concerts, and at festivals. Trips to the countryside on foot, by bike, with a sleeping bag, for an evening campfire, to balance out the busy city life. "Kde je v tomto meste výberová káva?"

Anna Puklová

About me:

I have been attracted to films since I was a child, so I ended up working in this field, at least partially. I started at KRUTÓN in 2023 as a distribution coordinator, but it soon became clear that I preferred working with children and on projects for children. I mainly lecture the Cinemini project for young audiences. Not only for this project, I prepare materials for teaching lessons and coordinate other teachers.

I studied International Relations and Media Studies at Charles University, and I try to work in both fields.

My favorites:

I love traveling and walking in the quiet woods, but I can't imagine living anywhere other than in the city. You'll usually find me with a book in one hand and a cup of coffee in the other, or by the pool.

Jan Patzak

About me:

I have been working at KRUTÓN since the beginning of 2023 – I started as a screener, then I was involved in the technical support of festivals and gradually became a permanent member of the team. I studied Film and Television Production at SPŠ ST Panská and am currently continuing my studies at VOŠ of Journalism. I make short films, work on various audiovisual projects, and dream of a career as a film director. I also do tattoos.

My favorites:

I love metal and techno, play bass guitar, and occasionally paint. My favorite directors are Lars von Trier and Darren Aronofsky–I have a soft spot for dark, emotionally charged films with a distinctive visual style.

Zbyněk Neumann

About me:

I joined the KRUTÓN in the summer 2023, when I was burned out from working in a corporate café and looking for a change. At that time, I had already worked as a projectionist in another Prague cinema and missed the cinema environment. I wanted to return to it, and quite by chance, I joined through a friend, as a position in cinema operator had become available, and we managed to combine my love for films, gastronomy, and drinks.

My favorites:

Climbing a hill in my native Krkonoše Mountains and watching the stars. Taking analog photos of nature. Long debates and film analyses where I can use fancy words like prism and discourse. Impulsive midnight cooking while watching anything from Anthony Bourdain to Cooking History. Making a half-liter of filter coffee from good quality beans in the morning, drinking it on an empty stomach, and wondering why I feel heavy...

Michaela Kubátová

About me:

I graduated in humanities and am currently studying comparative literature at Charles University. I have been a member of the KRUTÓN since 2023, where I first worked as a bartender at Kino Kavalírka and after less than a year I started working as an office manager.

When it comes to the world of film, I usually prefer books to film adaptations. I tend to seek out more demanding works in books, but when it comes to film, I prefer relaxing nostalgia, which for me means romantic comedies from the turn of the millennium.

My favorites:

Antique shops and second-hand stores, tea, yoga, piano, and dogs.

Martin Novotný

About me:

I graduated in Czech literature and social sciences from the Faculty of Education at Charles University, and I am currently studying social anthropology at the Faculty of Humanities at Charles University.

I have been part of KRUTÓN since 2023, when I started working as a bartender at Kino Kavalírka. One thing led to another, and I gradually began to take care of the websites of the projects that KRUTÓN runs and the newsletters.

My favorites:

I like bizarre Czech bands, spontaneous trips, cucumbers, and dogs. My guilty pleasure in movies is spaghetti westerns.

Anna Dočkalová

About me:

I studied Czech language and literature at Charles University and am continuing my studies in the same field. I have based my personality somewhat on literature – I like to give my friends little lectures on Kafka, or I often refer to Walter Benjamin, even though I don't really understand him.

My favorites:

When it comes to movies, I love The Graduate. I also like wine and hanging out in cafés, and I enjoy traveling. When I'm not talking about literature, I like to remind everyone how brilliant David Bowie is.

A brief story about how KRUTÓN came to be

When Filip Kršiak, Tereza Bonaventurová and Pepa Vičar founded KRUTÓN in 2015, the idea was simple: to create quality programmes - camps, workshops and smaller school projects - that would develop creativity and critical thinking in children and young people through working with film.

We started without great ambition, but with great commitment. We were united by the belief that film is an extraordinary tool - it offers a space for discovery, reflection and understanding of the world around us. We have been engaged in similar activities since 2010, and the creation of KRUTÓN was a natural continuation of this journey.

Krutónpolis and the key question

In 2016-2017, we opened Krutónpolis, a pop-up space for film education and a meeting place for film professionals in Prague's Vinohrady district, which lasted just over a year.

At the same time, we have been working on alternative distribution of European films, building a network of colleagues and started asking ourselves a fundamental question:

"Will KRUTÓN remain a small association or can it become a platform with a real impact?"

The decision was not an easy one - there was a lack of facilities, stable finances and it required personal sacrifices.

Friends asked us at the time, "Are you really going to make a living off rolls to do programs for kids?"

No one could imagine the future then. But as it happens with us, we decided to take the (most) difficult path - and started systematically building a professional and organizational foundation.

Tereza has since become a curator, Pepa a doctor - but both remain founding members and important advisors of the association.

What has changed since then?

- We created and ran the International Film Festival for Children and Youth Young Film Fest (Prague).

- We co-created the ELBE DOCK International Short Film Festival (Ústí nad Labem, Dresden).

- In 2025 we merged these two festivals into the BOO International Film Festival.

- Since 2021, we have been running the intimate boutique cinema Kavalírka.

- We participate in European projects and initiate our own - including systemic programmes aimed at long-term change in the field of audiovisual education.

- And much more...

KRUTÓN nowadays

Today, KRUTÓN is built on a solid team of experts who lead the various areas - from pedagogy, dramaturgy and industry programmes to international cooperation.

The key figures are Jana Minaříková, Executive Director, and Radka Hoffman, who develops international projects and relations with European partners. Our internal team, consisting of 15 colleagues and dozens of collaborators from all over the Czech Republic and Europe, also plays a crucial role.

Get to know OUR TEAM.

What remains

We have grown from a small initiative into an open platform that connects pedagogy, culture, research and practice - and offers new models of collaboration in the field of audiovisual education.

KRUTÓN continues to learn, transform and find new ways - rarely the simplest ones, often the ones that present real challenges.

And one thing remains: we always work for children, students, audiences, educators, professionals and audiovisual - with real commitment and an undying passion for the cause.

SATAN KINGDOM BABYLON

An experimental documentary by Petr and Marie Šprincl delves into the darkest corners of America’s hate-fueled subcultures, confronting the viewer with a visceral, sensory experience. Through a haunting mosaic of raw footage and interviews with cult leaders, the story follows a fictional detective investigating the disappearance of a young woman in a post-apocalyptic hotel. His search leads him deep into the world of the Ku Klux Klan, ultra-Orthodox Jews, Black Hebrews, and other religious movements of Trump’s America. The end is here.

directed by: Marie & Petr Šprincl screenplay: Marie Šprincl camera: Jan Vidlička music: Wojciech

Kucharczyk produced by: Marek Novák, Xova Film

About the directors

Marie & Petr Šprincl began their artistic collaboration during their studies at Václav Stratil's Intermedia Studio at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Brno. Today, they are a highly distinctive creative duo with a very characteristic style. Their work is characterized by unsettling poetics, drawing on the dark side of reality and working with 8mm film material or VHS tape, where the typical characteristics of the recording material, especially visual errors usually caused by wear and tear or structural damage, are objectified, aestheticized, and even fetishized. The audiovisual aspect of their work is usually complemented by rich iconography that transcends the medium of the moving image, which is given space for presentation within their creative platform Flesh&Brain. Their work balances on the border between fiction, documentary, and experiment, with a common feature being the exploration of various social forms of evil, often hidden beneath the thin veneer of everyday reality. They are the authors of the trilogy Moravia, O Fair Land (2015–2019), Vienna Calling (2018), or the current film Satan Kingdom Babylon (2024). In addition to films, they also work on music videos, theater performances, and gallery installations.

Satan Kingdom Babylon is Coming! Attend the Pre-premiere of New Experimental Documentary.

On Sunday, August 24, at 7 p.m., the unique Venuše ve Švehlovce theater will host a pre-premiere of Marie & Petr Šprincl's film Satan Kingdom Babylon.

An experimental documentary by Petr and Marie Šprincl delves into the darkest corners of America’s hate-fueled subcultures, confronting the viewer with a visceral, sensory experience. Through a haunting mosaic of raw footage and interviews with cult leaders, the story follows a fictional detective investigating the disappearance of a young woman in a post-apocalyptic hotel. His search leads him deep into the world of the Ku Klux Klan, ultra-Orthodox Jews, Black Hebrews, and other religious movements of Trump’s America. The end is here.

The gloomy atmosphere of the film will be complemented by the rondocubist interior of the historic theater hall. The screening will be accompanied by a discussion with the filmmakers, who spent two months among hateful groups in North America while shooting the film.

The evening will conclude with a raffle hosted by Ladislav Čumba. The prizes will vary and will not be related to the mood of the film. They will range from raw meat to mini golf vouchers.

🗓️ When: Sunday, August 24, 2025, at 7 p.m.

📍 Where: Venuše ve Švehlovce (Slavíkova 22, Praha 3)

🖇️ Follow the event on Facebook

About the directors

Marie & Petr Šprincl began collaborating as artists during their studies at Václav Stratil's Intermedia Studio at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Brno, and today they are a highly distinctive creative duo with a very characteristic style. Their work is characterized by unsettling poetics, drawing on the dark side of reality and working with 8mm film material or VHS equipment, where the typical characteristics of the recording material, especially image defects usually caused by wear and tear or structural damage, are objectified, aestheticized, and even fetishized. The audiovisual aspect of their work is usually complemented by rich iconography that transcends the medium of the moving image, which is given space for presentation within the Flesh&Brain creative platform. Their work balances on the border between fiction, documentary, and experiment, with a common feature being the exploration of various social forms of evil, often hidden beneath the thin veneer of everyday reality. They are the authors of the trilogy Moravia, Oh Fair Land (2015–2019), Vienna Calling (2018), or the current film Satan Kingdom Babylon (2024). In addition to films, they also work on music videos, theater performances, and gallery installations.

Cinetots in cinemas across the whole Czech Republic

And what makes our Cinetots selection so unique? First and foremost, because the films were selected by young film enthusiasts themselves! We have only selected films that have been successful at prestigious film festivals in recent years and then left the choice entirely up to our audience. This ensures that the line-up consists of films that really engage and entertain the audience and that we reflect current trends.

However, Cinetots is not just a selection of short films. We have also prepared worksheets that offer specially designed activities for each film, working with children's creativity and imagination to further deepen the experience of the film and help to place it in a wider educational context.

More information about the Cinetots, including free downloadable worksheets, can be found HERE.

Watch the documentary-making workshop with Barbora Chalupová

On 22 February 2025, an intensive half-day workshop for primary and secondary school teachers on the topic of genres in documentary film took place at the Kino Kavalírka. The workshop was led by Barbora Chalupová, co-director of the film Caought In the Net.

In addition to the theoretical preparation, the participating female teachers also tried to make their own short documentary film about the Kino Kavalírka within various documentary genres. Film posters were also created for each mini-documentary. The workshop ended with a reflection on the whole process and a screening of the films.

Film Academy: teach (with) film is part of the EU-funded international project FilmED which aims to promote audiovisual and film education in Central and Eastern Europe.

We are looking for a school projection coordinator and producer

Coordinator and producer of school screenings

Scope: a min of 0,5 time

Main task: coordination and organisation of school screenings for kindergartens, primary and secondary schools and production activities in the Audiovisual Department of the Kino Kavalírka

- communication with schools - teachers, principals, educational staff and school psychologists

- organisation of school screenings

- organisation of accompanying discussions, workshops and other activities

- co-creation of the film programme for schools

- taking care of established cooperation and establishing new contacts

- taking care of the film catalogue

- cooperation with internal and external lecturers

- cooperation on the promotion of school screenings

- production of school screenings

- participation in the programmes of the Audiovisual Education Department in other events (festivals, international events, etc.)

Advantage:

- orientation in film education or art education

- active interest in film and audiovisual culture

- good relationship with teachers, children and young people of all ages

- orientation in Czech education

- diligence and excellent communication skills

- openness to further education

Are you interested? Contact Adéla Lachoutová at edukace@krutonfilm.cz.

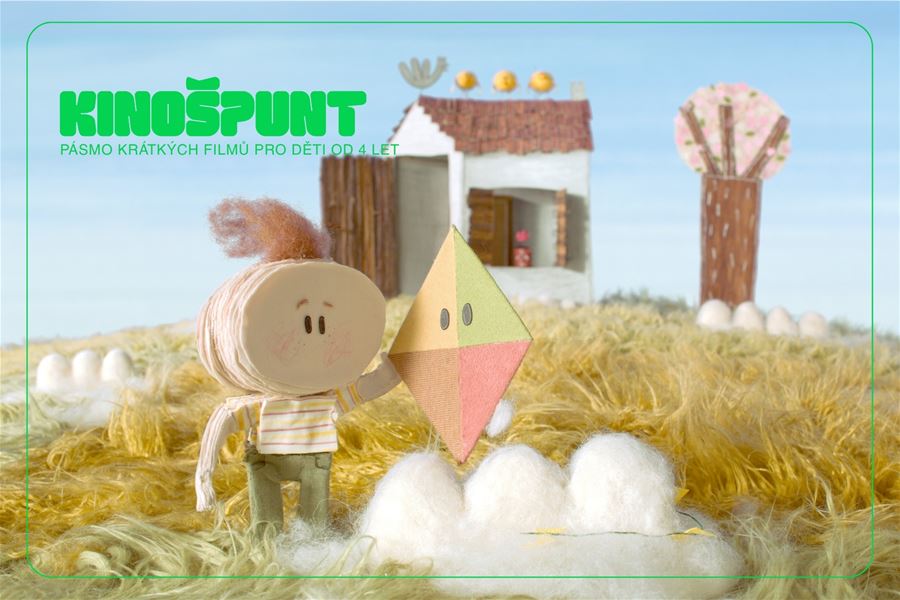

We also keep in mind the youngest CINETOTS: Young & Short 2025

For the first time ever, we have prepared a series of films for the youngest viewers aged 4 and up as part of the Young & Short project. The films were selected by young film jurors aged from 4 to 7 with the help of experienced lecturers. This ensures that Cinetots is not just a selection of films that caught the attention of jurors at international film festivals (Berlinale, Annecy, ECFA Award, DOK Leipzig, Clermont-Ferrand, etc.), but that they accurately reflect what young viewers enjoy and are interested in.

The program is suitable for families with children aged 4 and up, kindergartens, and all enthusiasts of children's and animated films.

For kindergartens and other educational institutions, we have also prepared worksheets that offer a wide range of creative activities for each film and provide methodological support for working with children's audiovisual experiences. In addition, we also organize interactive workshops and discussions at Kino Kavalírka. If you are interested, please write to us at edukace@krutonfilm.cz.

So what films can you look forward to? A Lynx in the Town shows what it's like when playfulness and curiosity collide with the "adult" world, where everyone just stares apathetically at their mobile phone screens, while Mr. Night Has a Day Off playfully depicts the changing parts of the day. Pond takes us on an underwater adventure, Black and White shows on cartoon sheep how far prejudice can take us, The Kite sensitively deals with the theme of the passing of a loved one, Hoofs on Skates teaches us that appearances can often be deceiving, and Fruits of Clouds depicts a story full of friendship and bravery.

Everything about the program, including the films, can be found HERE.

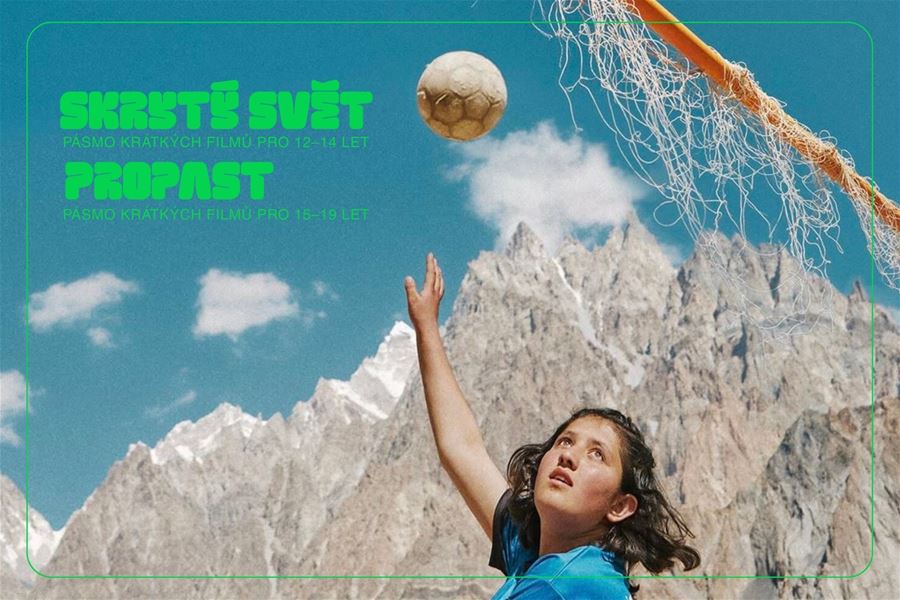

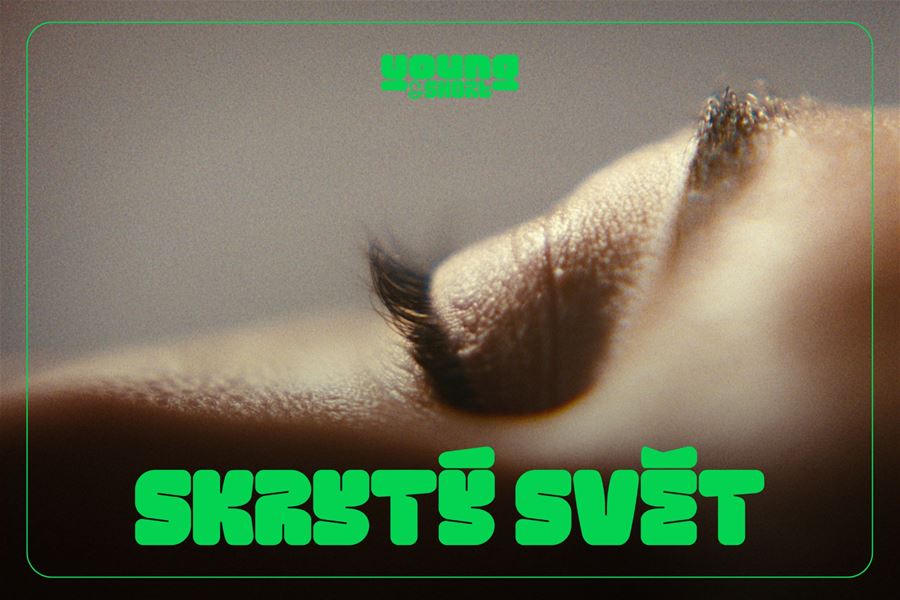

Exploring Hidden Worlds and bridging The Abyss: Young & Short 2025

The Hidden World programme was created by the young jurors themselves, aged 12 to 14. What was the main theme for them and why is the band called this? The common denominator of all the films is that they focus on exploring worlds that normally escape our eye. Either because of how distant they are to us, or simply because we don't think to look at things around us from a different angle.

The young jury has thus selected the most interesting short films that contemporary cinema has to offer and which have been successful across prestigious film festivals. The film A Body Called Life links the exploration of microscopic organisms with self-discovery, the colourful On the 8th Day develops environmental themes, Swimming with Wings gives a glimpse into the lives of Dutch migrant children through novel animation, Girls Move Mountains captures the incredible courage of Pakistani girls in their struggle for emancipation, and Touching Darkness through a special animation technique gives an insight into the lives of children with disabilities.

The Abyss strip is reflecting period of turbulent life changes at the turn of childhood and adulthood, when the teenage person gets to know themselves, but at the same time often faces the most difficult challenges of life so far and for the first time fully confronts existential questions. Young people aged 15 to 19 helped us to create the entire series, choosing from films that have attracted the attention of juries at leading festivals around the world (Berlinale, Clermont-Ferrand, Ottawa, as well as Oscar nominations, etc.).

The series thus reflects the theme of overcoming these imaginary life chasms, whether it is racial hatred shown in Butterfly, existential anxiety in Wander to Wonder, coping with the passing of loved ones in Phoenix, the self-discovering journey in Blood and Flowers, or the devastating effects of war depicted in I Died in Irpin.

The strips can be used as a whole, or you can create individual strips from the films based on their thematic focus, as well as combine them with strips from previous years (What If? and Carousel of Emotions).

DEADLINE for submission of visual identity proposals postponed to May 30

GRAPHICS TASKS

- festival poster

- mascot design - any kind of cow or ghost

- post on Instagram (the type of post is up to you, it can be a reveal of some part of the program, introduction of the creator or a guest of the festival, teaser to the festival site...)

- non-traditional format of your choice - it can be an interactive element, merch design, motion graphics, physical object, spatial installation or other creative way of visual communication of the festival

OPEN CALL PROCESS

- The deadline for submission of proposals is postponed to 30 May 2025.

- We will meet personally with the author of the selected proposal to discuss the terms of cooperation.

- The author of the selected proposal will receive a reward of 25.000 CZK for the delivery of the final concept and all necessary documents.

- Other participants will not be honoured.

- We reserve the right not to select any of the proposals if none of them corresponds to our ideas.

Please send your proposals to: julie@boofest.cz.

The full detailed specification and all information can be found HERE.

Invitation to the Speed Networking of Audiovisual Education

What can you expect?

- Quick and effective meetings in short blocks ("speed dating")

- Sharing of best approaches, challenges and ideas for collaboration

- Space for networking

- The event is free and open to all who want to develop audiovisual education together and are looking for partners for future projects, teaching or sharing experiences.

📅 When: May 15

📍 Where: Audiovisual HUB in Kino Kavalírka (Plzeňská 210, Prague 5)

🕓Time: 3:00 pm - 5:00 pm (+ aditional space for further networking after the event)

📝 Advance registration required. Please e-mail us on: edukace@krutonfilm.cz by May 12, 12:00 p.m.

💬 Come network - briefly, intensely and meaningfully.

We look forward to seeing you!

OPEN CALL for visual identity concept for BOO IFF

BOO FESTIVAL AND WHO IS BEHIND IT

The BOO International Short Film Festival was created through the transformation of the ELBE DOCK International Film Festival and the Young Film Fest International Film Festival for Children and Youth. The festival focuses on short cinema, audience development and audiovisual education. The first edition will be held in November 2025 in Prague and will take place in several venues, such as the Kino Kavalírka.

The association krutón is behind projects such as Young Film Fest, Young & Short, Kino Kavalírka or Cinemini - a film programme for children aged 4 and up. All of our activities are united by an emphasis on quality, cultural and social overlap, and a desire to bring film closer as a tool for knowledge, sharing and entertainment. We support non-profit projects that change the way we see the world through film, film education and audiovisual culture. Our projects are characterized by playfulness, unique humor and a desire to reach audiences of all generations.

As part of this open call, we are looking for a graphic designer or graphic artist who will conceptualize the visual identity of the festival - i.e. create the main graphic style, including mascots, logotype, color scheme and typography - while delivering easy-to-understand deliverables, templates and handouts for our in-house graphic designer to work with. He will take care of the concrete application of the visual across all outputs during the preparation and the festival itself.

GRAPHICS TASKS

- festival poster

- mascot design - any kind of cow or ghost

- post on Instagram (the type of post is up to you, it can be a reveal of some part of the program, introduction of the creator or a guest of the festival, teaser to the festival site...)

- non-traditional format of your choice - it can be an interactive element, merch design, motion graphics, physical object, spatial installation or other creative way of visual communication of the festival

OPEN CALL PROCESS

- The deadline for submission of proposals is 18 May 2025 (extended to 30 May).

- We will meet personally with the author of the selected proposal to discuss the terms of cooperation.

- The author of the selected proposal will receive a reward of 25.000 CZK for the delivery of the final concept and all necessary documents.

- Other participants will not be honoured.

- We reserve the right not to select any of the proposals if none of them corresponds to our ideas.

Please send your proposals to: julie@boofest.cz.

VISUAL IDENTITY CONCEPTUAL MEASUREMENT

Key Elements:

- We want the visual identity of the festival to include a mascot that reflects the name BOO. We are considering two options - a cow or a ghost, or creatively combining them into one element. The mascot should be a distinctive but not primary symbol of the festival.

Another key element of the visual is the festival logo, which should serve as a unifying element across communications. It already exists in its basic form, but its shape and colour scheme is not finalised, so we are open to new suggestions, modifications and original interpretation within the overall visual concept.

VISUAL IDENTITY APPLICATION

The visual identity of the festival will primarily focus on the online environment and digital marketing. Graphic communication on social media and other digital platforms will play a key role.

We also want the visual to be consistent across print and electronic materials such as:

- tickets and accreditation

- posters and printed materials

- social media graphics (posts, stories, reels)

It is important that the visual style unifies all these formats and creates a coherent visual impression of the BOO Festival.

Target groups:

The BOO Festival appeals to a wide range of audiences across generations - from 3 to 99 years old. Therefore, we want the visual identity to be universal enough to appeal to different age groups.

At the same time, we are considering the possibility of creating multiple variations of the visual identity that would be:

- Linked by a single element to keep the festival visually cohesive.

- Personalised for individual target groups, if it will be meaningful.

We leave the decision whether to differentiate the visuals to the graphic designers.

WHAT DO WE WANT TO AVOID?

Predictability

- We don't want the visual to look too generic or clichéd.

- Although we work with a cow or ghost, we still want the visual to be original and surprising.

Unintentional associations

- It's important to avoid visual similarities with well-known brands such as Milka or dating app Boo.

Cinemini on Czech Radio

Cinemini is a globally unique film education project for children aged 3 to 6, which will be implemented in our Kino Kavalírka from mid-2023. It is a combination of short, unconventionally conceived films and specially developed activities that will stimulate children's imagination and enhance their experience of the film. In a fun and meaningful way, we explore the world of film and audiovisual with children, developing their creativity, critical thinking and positive relationship to film from an early age.

Are you interested in what this looks like in practice? Listen to the report on the Czech Radio or visit the Cinemini project website.

Child Protection Policy - KRUTÓN

1. Introduction and values

The Krutón Association, as an organization operating in the field of audiovisual education and cultural education for children and young people, is committed to protecting children from all forms of violence, abuse, neglect, and other inappropriate treatment. The Child Protection Policy (hereinafter referred to as the "Policy") defines the principles, rules, and procedures that ensure a safe environment in all activities of the Krutón Association, especially in direct and indirect work with children.

The Policy is in accordance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Sb. z. č. 104/1991), the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms, the Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children (Sb. z. č. 359/1999 Sb.) and the general principles of the GDPR.

The krutón association promotes an approach based on the dignity of the child, their right to be heard, respected, and protected. The principles set out in this Policy are binding for all employees, associates, lecturers, volunteers, temporary workers, and external contractors who come into contact with children during the association's activities.

2. Definitions

Child:

A child is considered to be any human being under the age of 18, unless they have reached the age of majority earlier under the legal system.

Child protection:

A set of preventive and intervention measures and procedures aimed at ensuring the safety, dignity, and healthy development of children and preventing their abuse, neglect, or other endangerment.

Direct contact:

Physical presence at activities where there is interaction with a child (e.g., leading a workshop, discussion, filming, training, mentoring).

Indirect contact:

Mediated contact with a child through media, email, forms, photographs, or access to their personal data.

Child abuse:

Any intentional or unintentional behavior that may cause harm to a child's health, dignity, or development. It is divided into:

- physical (hitting, choking, burning, etc.),

- psychological (humiliation, intimidation, isolation, coercion),

- sexual (any sexual contact or proposition that a child cannot understand or give informed consent to),

- neglect (long-term neglect of care, nutrition, safety, and support).

Risk situation:

Any activity, environment, or relationship that could potentially expose a child to the above forms of harm.

3. Unacceptable behavior

When working with children, it is strictly prohibited to:

- engage in any form of physical, psychological, or sexual violence,

- treat children in a disrespectful, mocking, or humiliating manner,

- establish personal or private relationships with children outside the scope of professional contact,

- photographing or filming children without the express and informed consent of their legal representative,

- sharing or otherwise misusing children's personal data without authorization,

- leaving a child alone without adult supervision,

- exploiting imbalances of power or trust for personal gain,

- give children alcohol, addictive substances, or medication without medical indication,

- be alone with a child in a closed space without the presence of another adult or without

- ensuring that the interaction can be observed (e.g., open doors, visibility from the hallway, etc.).

4. Safe recruitment of employees and protection of personal data

4.1 Selection and verification of employees

Every person (employee, instructor, volunteer, external contractor) who participates in the activities of the krutón association and has direct or indirect contact with children must:

- sign a declaration of integrity (or provide a criminal record extract if required by the nature of the cooperation),

- sign a commitment to comply with this Policy and the Code of Conduct of the krutón association,

- undergo a personal interview to verify their knowledge of child protection principles,

- be familiar with the procedures for reporting incidents and suspected abuse.

The selection process is transparent and emphasizes the candidate's experience, competence, and values in relation to working with children.

4.2 Personal data protection (GDPR)

The Krutón Association protects the personal data of children and their legal guardians in

accordance with EU Regulation 2016/679 (GDPR). The organization:

- ensures that only designated persons handle children's personal data,

- obtains informed consent from parents or legal guardians for the processing of data, photographs, or audiovisual recordings,

- stores data in a secure manner (both electronically and physically),

- shares personal data only when required by law or when necessary to ensure the safety of the child.

5. Training and education

5.1 Initial training

Every new employee, instructor, volunteer, or other collaborator with direct or indirect contact with children must complete training on the following before starting work:

- the principles and objectives of the Child Protection Policy,

- recognizing forms of abuse and neglect,

- safe communication and interaction with children,

- the code of conduct of the Krutón association,

- procedures in case of suspected child safety violations (including the practical use of forms and reporting schemes).

5.2 Regular awareness-raising and refresher training

- Long-term collaborators shall undergo refresher training at least every two years.

- In the event of changes in legislation or updates to the Policy, special training will be provided to all affected persons.

- Internal trainers or the responsible person (see section 7) keep records of the persons trained and the dates of the training.

6. Revision of the document

This Child Protection Policy is subject to regular review to ensure that it remains up to date and is implemented effectively.

- Regular reviews of the Policy take place at least every three years, or sooner if there are changes in the law, significant events or incidents that require a change in procedure.

- The Child Protection Officer (see section 7) is responsible for the review in cooperation with the management of the krutón association.

- All employees, lecturers, volunteers, and partners affected by the change will be informed of the review and its results.

7. Responsible person – Child Protection Officer (CPO)

The person appointed by the association's management – the Child Protection Officer – is responsible for the implementation, training, monitoring, and evaluation of compliance with the Policy.

Responsibilities of the responsible person:

- ensures the training of new and existing employees,

- serves as the main contact person for consultation and reporting of suspicions or incidents,

- processes and archives reports of child safety violations,

- initiates reviews of the Policy and proposes amendments,

- actively monitors compliance with the rules and culture of safety within the krutón association,

- is listed in all places where contact with children occurs, including the organization's website.

The contact details of the responsible person will be publicly available online and at the venues where activities take place.

8. Procedures for reporting, complaints, and incident resolution

8.1 Duty to report

Every employee, instructor, volunteer, or external collaborator has a duty to immediately report any suspicion of abuse, inappropriate behavior, violation of rules, or other threat to a child.

Reports shall be submitted:

- to the person responsible for child protection,

- or the association's management if the responsible person is suspected of misconduct.

8.2 Forms of reporting

- Verbal reports must be immediately followed up with a written incident report form.

- The Policy includes a clear procedure diagram (algorithm) on how to proceed in such situations (Appendix 1).

- All documents are kept confidential, secure, and in accordance with the GDPR.

8.3 External protection systems

In serious situations or if a criminal offense is suspected:

- the organization is required to inform the relevant authorities (OSPOD, Czech Police),

- it may be recommended to contact the Safety Line, crisis centers, or other specialized services.

Emphasis is always placed on the best interests of the child, their safety, and trust.

9. Cooperation with external actors

The Krutón Association is part of a wider network of entities involved in child protection. If necessary, it cooperates with the following institutions:

- Social and Legal Protection of Children Authority (OSPOD)

- Czech Police

- Crisis centers and helplines (e.g., Safety Line 116 111, White Circle of Safety)

- Schools, school counseling facilities

- Non-governmental organizations focused on prevention and assistance to children

In the event of serious suspicion that a child is at risk, the organization will actively cooperate with the relevant authorities, provide the necessary information, and strive to protect the child as quickly and effectively as possible.

The association also seeks partnerships for training, methodological development, and prevention of risky behavior with organizations that share the values of children's rights.

10. Availability of the document

10.1 Public access

This Policy will be:

- published in full on the Krutón Association website,

- available in printed form at all locations where activities with children take place,

- included in the introductory information package for new employees, lecturers, and volunteers.

10.2 Child friendly version

The krutón association will create a simplified and visually appealing version of the document for children and young people, which will:

- explains their rights, how to protect themselves, and who to turn to,

- be available in print and online,

- be presented to children at the beginning of each longer activity or program.

In this way, the association ensures that children not only have a protected environment, but also access to information and the confidence to express their concerns or suggestions.

Form for reporting suspected child protection violations, adapted for the krutón association and including the name of the responsible person:

📝 ANNEX 1: RECORD OF SUSPECTED CHILD PROTECTION VIOLATIONS

This form is used for internal recording of suspected threats to the safety or rights of children within the activities of the krutón association. The completed form must be forwarded immediately to the person responsible for child protection.

1. INFORMATION ABOUT THE PERSON MAKING THE REPORT

(name, position in the association, contact details – email or telephone)

.........................................................................................

.........................................................................................

2. DATE AND TIME OF THE RECORDED EVENT / SUSPICION

Date: .......................................................

Time: ...........................................................

3. PLACE OF THE EVENT (if known)

.........................................................................................

4. DESCRIPTION OF THE EVENT / SUSPICION

(what happened, what was said or observed – as specifically as possible, without speculation)

..............................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................

5. WHO WAS PRESENT AT THE EVENT / WITNESSES

(names, positions – if known)

.........................................................................................

.........................................................................................

6. STEPS ALREADY TAKEN

(e.g. contacting parents, calming the situation, taking the child to safety, etc.)

.........................................................................................

.........................................................................................

7. RECOMMENDATIONS / SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER ACTION (optional)

.........................................................................................

.........................................................................................

8. SIGNATURE OF THE PERSON MAKING THE REPORT

.............................................................

(name and date)

THIS FORM WILL BE DELIVERED TO AND KEPT BY THE PERSON RESPONSIBLE FOR CHILD PROTECTION:

Jana Minaříková, Executive Director of the Krutón Association (jana@krutonfilm.cz)

BINDING DECLARATION OF ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF THE CHILD PROTECTION POLICY

Krutón Association – organization for audiovisual education and upbringing of children

I, the undersigned, hereby declare that:

- I have been familiarized with the document Child Protection Policy – krutón association and have thoroughly familiarized myself with its contents.

- I understand the rules and principles set out in the Policy, including the Code of Conduct, the definition of inappropriate behavior, and the procedure to follow in case of suspected child safety violations.

- I agree to follow all the rules and principles set out in the Child Protection Policy and will always act in the best interests of the children.

- I agree to cooperate with the responsible person, especially if there is a suspicion of child endangerment or other risky behavior.

- I solemnly declare that I have not been convicted of any criminal offense against a child or of any offense related to sexual freedom, violence, or child neglect.

- I agree that, if necessary, I will provide an extract from the Criminal Register or other proof of good character if required by the nature of my cooperation with the krutón association.

Date: .................................................

Full name: .............................................................

Position / Role in the krutón association:: .................................................

Signature: .............................................................

I confirm that I have signed this document voluntarily and truthfully.

This record is kept and archived by the person responsible for child protection:

Jana Minaříková, Executive Director of the krutón association

I HAVE THE RIGHT TO BE SAFE

Information for children and young participants in krutón association activities

📌 Your rights

When participating in krutón association activities (e.g., workshops, filming, screenings, or

games), you have the right to:

- feel safe,

- be respected and listened to,

- speak up if something makes you uncomfortable,

- be protected from bullying, harm, or humiliation.

❗ What is inappropriate behavior?

If someone behaves in the following ways, it is not okay:

- shouts at you or ridicules you,

- wants to be alone with you and you don't want to be alone with them,

- touches you in a way that makes you feel uncomfortable,

- does not want to let you go home or prevents you from contacting your parents,

- tells you not to tell anyone about something.

🗣️ What can you do if something makes you feel uncomfortable?

- Tell an adult you trust – for example, a leader or instructor.

- If you are afraid or unable to do so, write a message or ask a friend to accompany

you.

👩💼 Who you can contact directly:

Jana Minaříková

Child Protection Officer

📧 jana@krutonfilm.cz

❤️ Remember:

💬 Your opinion matters.

🙋 If something is wrong, you can speak up.

🛡️ Everyone has the right to be safe – including you.

Prague Audiovisual HUB opened

Audiovisual education is one of the most dynamically developing trends in contemporary education. According to a Safer Kids Online survey, almost two-fifths of teenagers spend between 4 and 9 hours a day on audiovisual content. One of the concrete steps to respond to this trend is the opening of the Audiovisual HUB in the Kino Kavalírka in Prague, which was established in pilot mode on 1 August 2024 and is now opening up to a wider professional and pedagogical community and joining the emerging network of regional HUBs across the Czech Republic.

The Audiovisual HUB will serve as a centre for methodological support, research, teacher training, examples of good practice and advocacy. In connection with the newly prepared Framework Educational Programmes, it will assist schools in introducing new forms of media and cultural literacy into teaching - in addition to music and art education, it will also now include film, drama and dance.

Behind the creation of the Audiovisual HUB is the association krutón, which runs the Kino Kavalírka, distributes short films for children and youth, implements the international educational projects Cinemini and FilmED, and is the organiser of the new BOO International Film Festival. The Audiovisual HUB is the result of two years of research into foreign approaches and methodologies, taking inspiration from, for example, the Dutch Film HUB network.

"We spent two years researching models of good practice abroad. We have created a place that is dedicated not only to film, but also to broader audiovisual education - from short films to video games to testing methodologies. The HUB will also serve as a contact and methodological centre for educators and experts from Prague," says Filip Kršiak, chairman of the krutón association.

Jana Minaříková, executive director of the krutón association, adds: “The HUB in Prague is primarily a place of cooperation and search for systemic solutions - we translate and adapt foreign methodologies, share examples of good practice, provide advice to schools and establish partnerships with representatives of the film and video game industry.”

The project has a strong international dimension thanks to Radka Hoffman, Head of International Relations and Industry Programmes at krutón, who has been newly elected to the board of the European Children's Film Association (ECFA), Europe's most prestigious children's film organisation. Her task is now to actively connect Czech and European actors in the field of film and audiovisual education and to create a space for joint projects, sharing experiences and mutual inspiration.

The opening of the HUB is part of a broader strategy for the development of film and audiovisual education coordinated by the Association for Film and Audiovisual Education. The project was created in partnership with the krutón association and the Documentary Film Centre in Jihlava and was supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic. The Minister of Culture Martin Baxa signed a memorandum of cooperation with the Association for Film and Audiovisual Education, which enables further systematic development of audiovisual education across regions and institutions and its deeper embedding in the education system. In addition to Prague, other HUBs are currently being established in Jihlava and Brno.

Kino Kavalírka cinema

Prague's one-screen boutique cinema with a unique atmosphere and comfortable retro armchairs five minutes by tram from Anděl metro station.

The Na Zámečnici cinema was established in the 1930s and closed down in the early '90s. In 2021, our association krutón, z.s. managed to revive the cinema, and since 2022 it has been open all year round. We have renamed the cinema to Kino Kavalírka , referring to the former film studios in Kavalírka.

The programme includes contemporary film news, special screenings combining films with a gastronomic experience or creation (FILM & DRINK, FILM & DEGUSTATION, FILM & CRAFT), bizarres and internet phenomena, as well as thematic film cycles, showcases and film festivals. Even the youngest ones will find something to do here, for whom, in addition to the standard distribution screenings, we also organise a regular CINEMINI club. We also offer our Young & Short film education programmes for kindergartens, primary and secondary schools.

The cinema also has a bar with a wide range of gins from Czech distilleries, alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks made from quality ingredients, non-alcoholic beers, but you can also enjoy draft beer specials, wines from Czech winemakers or the best Czech cidre. In the summer months, the bar moves outside to the courtyard garden, where you can relax in the shade of full-grown chestnut trees. You can have a drink just like that or take it with you to the cinema to watch a movie.

BOO International Short Film Festival

More about the BOO IFF can be found HERE.

The BOO International Short Film Festival was created by merging two International Film Festivals ELBE DOCK and Young Film Fest and its first year will take place from 3 to 9 November 2025 in Prague.

The festival's dramaturgy is based on a selection of films from the most prestigious film festivals (Cannes, Venice, Locarno, Clermont-Ferrand, Berlinale, Sundance, Toronto, Oscar nominations), but also gives space to emerging talents. In addition, the industry programme will also play an important role, focusing on short films and audiovisual education.

You can look forward to a total of six competition categories in which contemporary short films will compete. The two main competition categories are the pan-European and Czech-German sections, which follow the tradition of the ELBE DOCK festival, in which the Czech-German programme had a special place alongside the pan-European programme. In addition to these two categories, films can also compete in the categories for children aged 3 years and older, two categories for young people (12-14 and 15-19 years), as well as in the category of films for seniors.

What makes BOO different from other film festivals? First of all, its approach to the audience, which tries to involve them as much as possible and actively lead them to an open dialogue, while also placing great emphasis on the peer-to-peer method, which consists in sharing experiences between members of the same age or professional group.

Another thing in which BOO excels is its industry program, where it will bring a rich industry program focused on short film. And most importantly, a pan-European program focusing on audiovisual education and best practice examples from abroad. So you can look forward to a wide range of topics from the worlds of audiovisual education and short film, presented by leading experts from all over Europe.

KRUTÓN LAB

KRUTÓN LAB is a living ecosystem: we explore new methods and formats, test them directly with students and teachers, share our know-how with cultural institutions, and engage creators and experts. We work with data to better understand the needs of audiences and the professional sphere, and contribute to systemic changes in the field of audiovisual literacy.

What does KRUTÓN LAB encompass?

- Audiovisual Centre (2021–2025) – support for professionals, formerly known by the longer name Centre for Innovation and Cultivation of the Audiovisual Environment

- Audiovisual HUB (from 2024) – a project to support teachers and infrastructure in the field of film education

- Visegrad Audiovisual LAB – international cooperation within the V4 countries. The project includes the key International Day of Audiovisual Education.

- FilmED (2024–2025) – European project for the development of methodology for teachers and cultural workers

- Audiovisual Connect LAB (2026–2027) – European project exploring literacy, linking education with professional practice.

Our goals

- To develop film and audiovisual literacy among children, young people, and adults;

- to support teachers, creators, cinema operators, festivals, and cultural professionals;

- to bring European film and audiovisual content into schools and public spaces;

- to create a sustainable model of education and professional cooperation based on research and data.

Cinemini

Cinemini is a globally unique project that was originally created in 2019 in the Netherlands and Germany and which we brought to the Czech Republic in 2023. The project deals with film and audiovisual education for preschool children aged 3 - 6 years.

What to imagine by this? Our lecturers will show several short films to the children, which represent a variety of cultures and approaches to film. After each screening, the children share together, under the guidance of the tutor, the feelings, impressions and thoughts that the film has evoked in them. The discussion is then followed by activities that have been prepared specifically for each film to further enhance the experience of the film.

And why is this so important? Children today come into intense contact with audiovisual content on a daily basis from an early age, so it is important that they learn to think critically about it and to name the feelings it evokes in them. Moreover, the pre-school age is a time when children, thanks to their unique imagination, perceive audiovisual stimuli very intensely and in a very different way from later in life, and this age is therefore crucial for the development of their imagination and fantasy.

We organize screenings for kindergartens and first grade all over the country and also in our Kino Kavalírka cinema, where we also organize a regular child club for the public from February 2025. If you are interested in school screenings or registering for a club, please contact us at edukace@krutonfilm.cz.

Audiovisual Centre

About the project

In 2021, we established the Center for Innovation and Cultivation of the Audiovisual Environment, which operated under this name until 2022 and was supported by the EEA and Norway Grants. In 2023, the name was shortened to Audiovisual Center.

It is a platform that offers film and video game professionals, critics, and the public guidance in the ever-changing audiovisual industry. Workshops, lectures, industry brunches, and conferences are held here.